The fate of marine plastics in subtropical waters

Short summary

Plastic pollution in our oceans is a critical issue affecting marine life, human health, and economies dependent on coastal tourism and fisheries. Plastics, primarily derived from petrochemicals, are omnipresent due to their versatility and durability. The surge in plastic demand has led to a significant increase in waste, especially of common polymers like polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene (PS). These materials often end up as marine debris, originating from both land and sea activities.

Marine plastic debris (MPD) not only litters the surface but also sinks to the ocean floor, posing a long-term environmental challenge. Biofouling, the process where microorganisms colonize plastic surfaces, facilitates this sinking. The interaction between plastics and microbial communities is complex, with some microbes potentially capable of degrading plastics, though this process is not fully understood.

A study focusing on subtropical coastal waters in the Caribbean and Mediterranean Sea investigated the factors influencing plastic degradation. We found that the type of plastic and environmental conditions significantly affect microbial colonization and degradation. We used advanced techniques like 16S rRNA gene sequencing and stable isotope tracing to track microbial activity and plastic-derived carbon assimilation.

Results showed that while microbial communities vary initially based on polymer type, environmental factors like location and habitat have a more substantial impact over time. Additionally, photodegradation through UV radiation plays a crucial role in breaking down floating plastics, highlighting the need for further research to understand its ecological impacts.

Broader implications

The findings on microbial colonization and degradation can aid in developing biodegradable plastics that are more effectively broken down in marine environments. Similar to the biodegradation of non-biodegradable polymers, microbial breakdown of biodegradable polymers may yield different compounds that could pose potential harm. When managed with defined end-of-life scenarios, especially if derived from renewable resources, biodegradable polymers could contribute significantly to a circular and more sustainable plastic economy. Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize that they do not offer a definitive solution to reduce future marine plastic pollution.

Insights into UV-induced photodegradation highlight the need to consider solar radiation in plastic pollution models and its impact on marine ecosystems. To fully understand the consequences of photooxidation of MPD, it is crucial to further constrain the effects of dissolved organic carbon and nanoplastic release into marine environments. This includes further research into plastic leachates and their impact on and degradability by microbial life.

Research presented in this thesis indicates that the microbial plastic breakdown proceeds at a slow rate in aquatic medium under controlled settings, and this process is expected to be even slower in natural environments due to less optimal conditions like temperature variations and limited presence of plastic-degrading microbes. While the concept of microbial plastic bioremediation in nature is enticing, practical in situ bioremediation appears viable only in highly concentrated and localized plastic pollution areas, such as landfills or polluted soils. The rates of biotic and photodegradation of plastics suggest that employing UV-based filters could be a more practical solution for addressing plastic pollution in waste water treatment plants, at least until highly efficient microbes/enzymes have been identified or engineered.

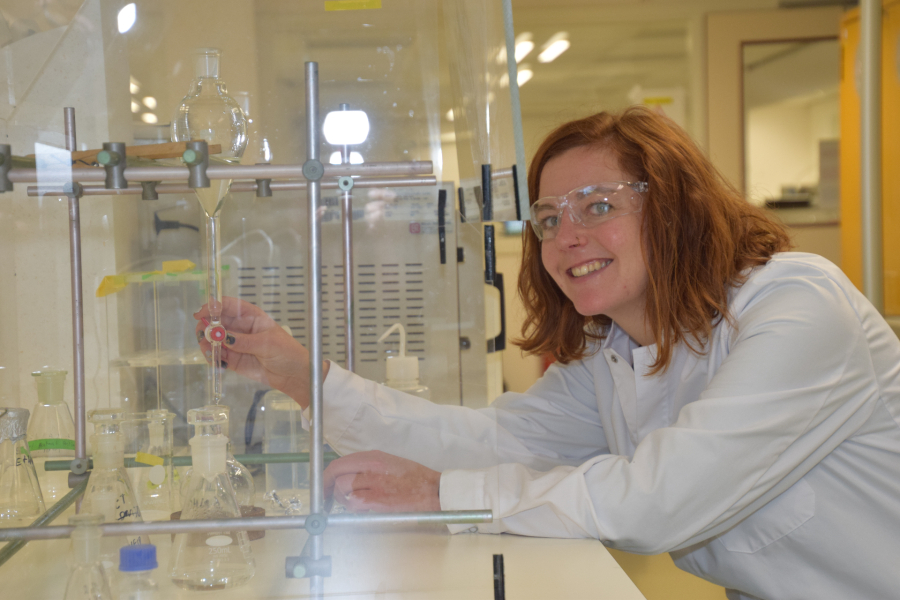

PhD Defence Maaike Goudriaan

Title: Microbial colonization, biodegradation, and photodegradation of marine plastics in (sub)tropical waters

PhD supervisors:

- Prof. Dr Helge Niemann

- Prof. Dr Ir Jaap Sinninghe Damsté

Practical information

Date: Wednesday 2 October 12:15

Location: Academy Building, Utrecht University

More information and the link to the livestream

Related news

Bacteria really eat plastic