Genetic insights shed light on shiny bacteria

Structural colour

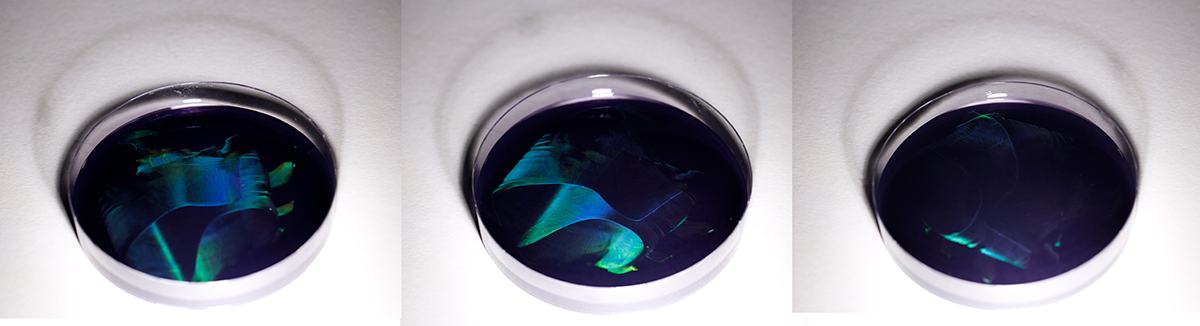

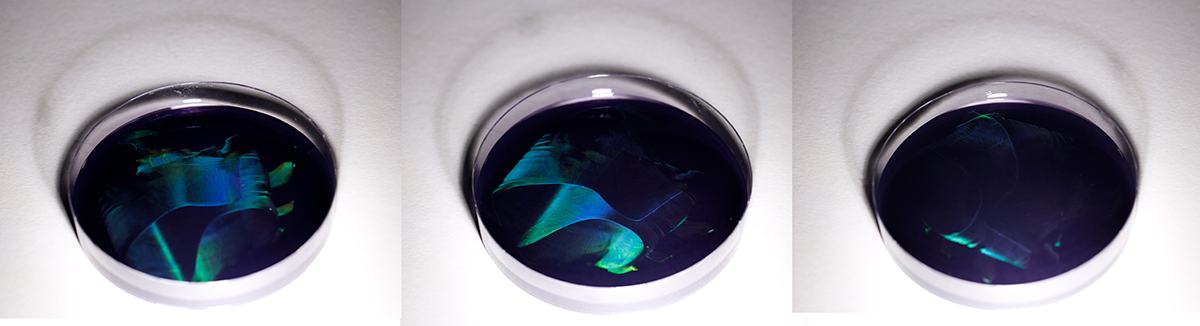

The striking, vibrant colours that we know from butterfly wings and peacock feathers are not the result of dyes or pigments. Instead, they are created by tiny, ordered structures that interact with light, creating a vibrant display of hues that is often perceived as iridescence (changes in colours depending on the angle of view or illumination). Such ‘structural colour’ is widespread in nature, and also exist in bacteria.

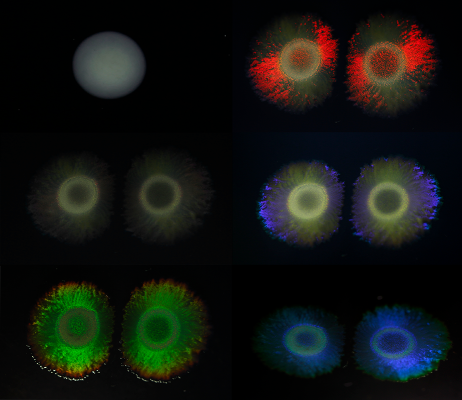

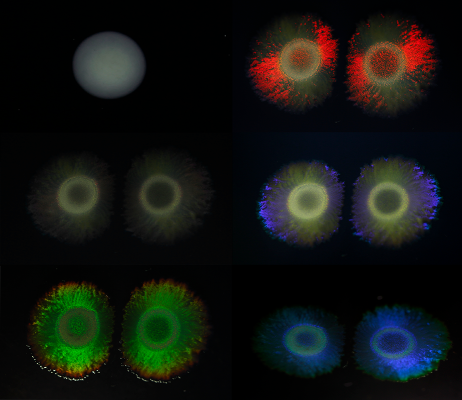

Structural colour is not displayed by individual single-cell bacteria, but by colonies of certain bacteria. Previous studies showed that specific genes involved in motility allow these bacteria to precisely align and form highly structured colonies that are able to produce iridescence. The exact function of structural colour in bacteria, as well as the genetics behind them, remained largely unknown up to now. In other life forms, structural colour plays a role in display, camouflage or protection from light, amongst others.

Specific genes

To gain more insight into the genetics behind structural colour in bacteria, the first step the researchers took was to collect 87 structurally coloured bacterial isolates, alongside 30 closely related non-iridescent strains. They then determined the sequence of the DNA of these bacteria. By comparing the DNA-sequences of the different strains, the researchers found that the bacteria that exhibited structural colours shared specific genes, even though the iridescent bacteria belonged to very diverse and different bacterial groups. These genes were absent in non-iridescent bacteria.

“This suggested that genes leading to structural colour may be shared between bacteria that are not directly related,”, says Bas Dutilh, professor at the University of Jena and visiting professor at Utrecht University. “Being able to trace the evolution of this colony characteristic, which is so striking to us, may help us to understand its function in bacteria.” Interestingly, some of the genes that were associated with structural colour in bacteria also contribute to the phenomenon in butterfly wings.

Machine learning

Combining the genetic insights with the data of the 117 DNA-sequences, the researchers also trained a computer model to be able to predict whether bacteria would display iridescence based only on their DNA-sequence. They used a technique called machine learning, a form of artificial intelligence that uses mathematical models to allow computers to learn without giving them direct instructions. “The machine learning model unexpectedly also predicted structural colour in new groups of bacteria, which we confirmed in the lab. This really shows the power of machine learning to predict biological functions from very complex genetic data”, says UU-researcher Aldert Zomer.

Distribution of structural colour

Bastiaan von Meijenfeldt, currently working at NIOZ but at the time a PhD student in Utrecht, used this machine learning model to analyse the DNA of all kinds of other bacteria. He screened and analysed 250,000 publicly available bacterial DNA-sequences and 14,000 metagenomes, which are complete sets of DNA-sequences found in environmental or clinical samples. Using this data, Von Meijenfeldt set out to map the distribution of structural colour in the bacterial tree of life, and across habitats.

The researcher found that bacteria that live in or on hosts, such as our gut bacteria, almost never showcase structural colour. In contrast, structural colour was predicted to be abundant in bacteria that live in marine waters and lakes, and in interfaces between surface and air such as on glaciers and in intertidal areas. The latter finding could suggest that the function of the structuring in these bacterial colonies is indeed to interact with light. However, this does not always seem to be the case.

More colour in deeper water

Von Meijenfeldt: “We were very surprised to see that the abundance of genes involved in structural colour increased in bacteria living in deeper waters, where light does not penetrate. This is not what you would expect if breaking of light plays a role in bacterial structural colour. We did find support for a hypothesis that bacterial structural colour is associated with floating particles in these dark depths, which potentially could mean that the structuring has other advantages and structural colour in this case is a byproduct.”

Interdisciplinary research project

The study is the result of a large scale and highly interdisciplinary collaboration between institutes, initiated by Henk Bolhuis who received a ZonMW grant for this earlier. “We were intrigued by these strikingly coloured, reflective bacterial colonies, and we wondered how widespread this phenomenon was.” Bolhuis’ knowledge on marine micro-organisms was combined with the expertise from the team in Utrecht in machine learning and genomics: the field that focuses on the study of the complete set of DNA of organisms. Richard Hahnke (Leibniz Institute DSMZ) contributed rare bacterial isolates and Silvia Vignolini (University of Cambridge and Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces) performed experiments that proved the colony structuring.

Nieuw licht op schitterende bacteriën

Publicatiedatum: Donderdag 12 juli 2024

Sommige bacteriën vormen opvallend gekleurde, reflecterende kolonies. Een internationaal en interdisciplinair team met onder andere NIOZ-onderzoekers Henk Bolhuis en Bastiaan von Meijenfeldt, verkreeg nieuwe genetische inzichten in hoe deze kleuren door bacteriën worden gevormd, en kon daarmee in beeld te brengen in welke leefomgevingen en bacteriegroepen zulke kleuren voorkomen. De bevindingen, die zijn gepubliceerd in het wetenschappelijke tijdschrift Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), geven aanwijzingen over wat de functie van kleuren bij bacteriën zou kunnen zijn, en kunnen mogelijk bijdragen aan de ontwikkeling van nieuwe innovatieve materialen om niet-duurzame kleurstoffen te vervangen.

Structurele kleur

De opvallend, intense kleuren die we kennen van vlindervleugels en pauwenveren zijn niet het resultaat van pigmenten of kleurstoffen. Ze ontstaan door minuscule, geordende structuurtjes die het licht op zo’n manier weerkaatsen dat er een levendig kleurenspel ontstaat. Dit fenomeen wordt dan ook structurele kleur genoemd. Bij structurele kleur zie je afhankelijk van de hoek waarop je kijkt vaak andere kleuren, een effect wat iriseren wordt genoemd. Structurele kleur komt wijdverspreid voor in de natuur, en dus ook bij bacteriën.

Individuele, eencellige bacteriën vertonen geen structurele kleur, alleen kolonies van bepaalde bacteriën doen dat. Eerdere studies tonen aan dat specifieke genen die betrokken zijn bij hoe deze bacteriën zich bewegen, de micro-organismen in staat stellen om zich nauwkeurig te ordenen en zo zeer gestructureerde kolonies te vormen die iriserende kleuren kunnen produceren.

Wat precies de functie is van structurele kleur bij bacteriën en welke genen er verder bij betrokken zijn, is voor het grootste deel nog niet bekend. Bij andere levensvormen speelt structurele kleur onder andere een rol bij de communicatie, camouflage of bescherming tegen licht.

Specifieke genen

Om meer inzicht te krijgen in de genetica achter structurele kleur bij bacteriën, verzamelden de onderzoekers eerst 87 structureel gekleurde bacteriën en 30 nauw verwante niet-iriserende bacteriën. Vervolgens bepaalden ze de volgorde van het DNA van deze bacteriën. Door de DNA-volgordes van de verschillende soorten te vergelijken, ontdekten de onderzoekers dat de bacteriën die structurele kleur vertoonden specifieke genen deelden die afwezig waren bij niet-iriserende bacteriën, ook al behoorden de iriserende bacteriën tot allerlei verschillende bacteriegroepen.

“Dit wijst erop dat genen die leiden tot structurele kleur mogelijk uitgewisseld worden tussen bacteriën die niet direct verwant zijn”, zegt Bas Dutilh, hoogleraar aan de universiteit van Jena en gasthoogleraar aan de Universiteit Utrecht. “Dat we de evolutie van dit voor ons zo opvallende koloniekenmerk kunnen volgen, kan ons helpen te begrijpen wat de functie ervan is bij bacteriën.” Opvallend genoeg bleken sommige van de genen die gelinkt waren aan structurele kleur bij bacteriën, ook bij te dragen aan het fenomeen in vlindervleugels.

Machine learning

Door de genetische inzichten te combineren met de gegevens van de 117 DNA-volgordes, trainden de onderzoekers een computermodel dat, puur op basis van hun DNA-volgordes, kon voorspellen of bepaalde bacteriën iriserend zijn. Ze gebruikten een techniek die machine learning wordt genoemd, een vorm van kunstmatige intelligentie die wiskundige modellen gebruikt om computers te laten leren zonder ze directe instructies te geven. “Het machine-learning model voorspelde ook structurele kleur in nieuwe groepen bacteriën waarvan we het niet verwacht hadden. In het lab hebben we bevestigd dat deze bacteriën inderdaad iriserend zijn. Dit toont echt de kracht van machine learning, waarmee het mogelijks is om biologische functies te voorspellen uit zeer complexe genetische gegevens", aldus UU-onderzoeker Aldert Zomer.

De verspreiding van structurele kleur

Bastiaan van Meijenfeldt, indertijd promovendus in Utrecht maar inmiddels verbonden aan het NIOZ, liet het machine-learning model vervolgens los op het DNA van allerlei andere bacteriën. In totaal analyseerde hij 250.000 bacteriële DNA-volgordes en 14.000 metagenomen, dat zijn complete sets DNA-volgordes afkomstig uit omgevings- of klinische monsters. Zo bracht Von Meijenfeldt in kaart waar structurele kleur te vinden is in de stamboom van het bacteriële leven en in allerlei leefomgevingen.

De onderzoeker ontdekte dat bacteriën die in of op gastheren leven, zoals onze darmbacteriën, bijna nooit structurele kleur vertonen. Structurele kleur werd daarentegen veel voorspeld bij bacteriën die leven in zeewater en meren, en in overgangsgebieden tussen oppervlaktes en lucht, zoals op gletsjers en in intergetijdengebieden. Dit laatste zou erop kunnen wijzen dat deze bacteriekolonies gestructureerd zijn zodat ze licht kunnen weerkaatsen. Maar dit lijkt niet in alle gevallen zo te zijn.

Von Meijenfeldt: “We waren erg verrast om te zien dat het aandeel genen dat een rol speelt in structurele kleur toenam in bacteriën die leven in diepere wateren, waar licht niet doordringt. Dit is niet wat je zou verwachten als het weerkaatsen van licht een rol speelt. We vonden wel steun voor een hypothese dat structurele kleur bij bacteriën vaak voorkomt bij drijvende deeltjes in deze donkere diepte, wat mogelijk zou kunnen betekenen dat de structurering hier andere voordelen heeft en structurele kleur in dit geval een bijproduct is.”

Interdisciplinair onderzoek

Het onderzoek is het resultaat van een grootschalige, interdisciplinaire samenwerking tussen verschillende instituten. De samenwerking was opgezet door NIOZ-onderzoeker Henk Bolhuis, die hier eerder een ZonMW-subsidie voor ontving. “We raakten geïntrigeerd door de opvallend gekleurde, reflectieve bacterie kolonies en vroegen ons af hoe wijdverspreid dit bijzondere fenomeen is”. Bolhuis’ kennis over mariene micro-organismen werd gecombineerd met de expertise van de Utrechtse onderzoekers op het gebied van machine learning en genomics: het vakgebied dat zich richt op bestuderen van de complete set DNA van organismen. Richard Hahnke (Leibniz Instituut DSMZ) leverde zeldzame bacteriële isolaten aan en Silvia Vignolini (University of Cambridge and Max Planck Institute of Colloids and Interfaces) voerde experimenten uit die de structurering van de kolonies aantoonden.

The paper 'Structural color in the bacterial domain: The ecogenomics of a 2-dimensional optical phenotype' by Aldert Zomer, Colin J. Ingham, F. A. Bastiaan von Meijenfeldt and Bas E. Dutilh was published in PNAS on 11 July 2024.

doi: 10.1073/pnas.2309757121.

De Nederlandse vertaling van dit persbericht vindt u onderaan deze pagina