Fungus breaks down ocean plastic

Fungus breaks down ocean plastic

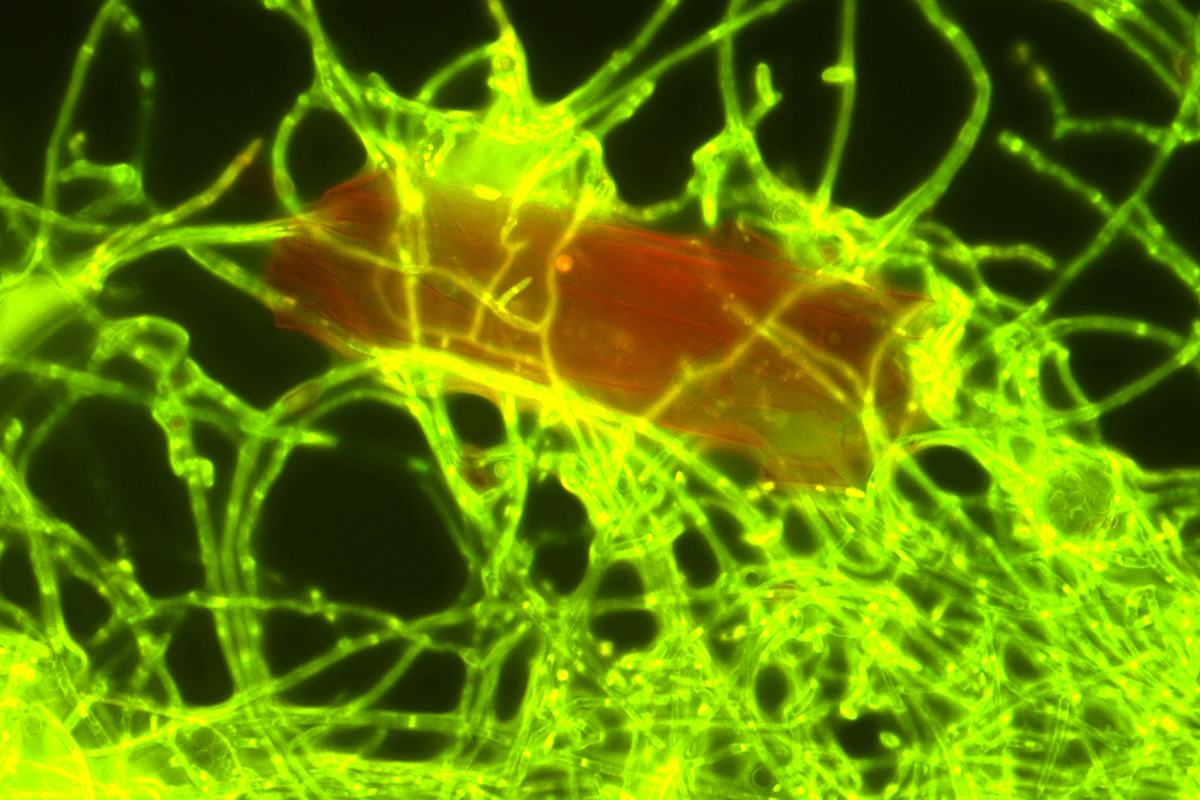

The fungus Parengyodontium album lives together with other marine microbes in thin layers on plastic litter in the ocean. Marine microbiologists from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ) discovered that the fungus is capable of breaking down particles of the plastic polyethylene (PE), the most abundant of all plastics that have ended up in the ocean. The NIOZ researchers cooperated with colleagues from Utrecht University, the Ocean Cleanup Foundation and research institutes in Paris, Copenhagen and St Gallen, Switzerland. The finding allows the fungus to join a very short list of plastic-degrading marine fungi: only four species have been found to date. A larger number of bacteria was already known to be able to degrade plastic.

Follow the degradation process accurately

The researchers went to find the plastic degrading microbes in the hotspots of plastic pollution in the North Pacific Ocean. From the plastic litter collected, they isolated the marine fungus by growing it in the laboratory, on special plastics that contain labelled carbon. Lead author Annika Vaksmaa of NIOZ: "These so-called 13C isotopes remain traceable in the food chain. It is like a tag that enables us to follow where the carbon goes. We can then trace it in the degradation products.”

Vaksmaa is thrilled about the new finding: “What makes this research scientifically outstanding, is that we can quantify the degradation process.” In the laboratory, Vaksmaa and her team observed that the breakdown of PE by P. album occurs at a rate of about 0.05 per cent per day. "Our measurements also showed that the fungus doesn’t use much of the carbon coming from the PE when breaking it down. Most of the PE that P. album uses is converted into carbon dioxide, which the fungus excretes again.” AltThough CO2 is a greenhouse gas, this process is not something that might pose a new problem: the amount released by fungi is the same as the low amount humans release while breathing.

Only under the influence of UV

The presence of sunlight is essential for the fungus to use PE as an energy source, the researchers found. Vaksmaa: “In the lab, P. album only breaks down PE that has been exposed to UV-light at least for a short period of time. That means that in the ocean, the fungus can only degrade plastic that has been floating near the surface initially,” explains Vaksmaa. “It was already known that UV-light breaks down plastic by itself mechanically, but our results show that it also facilitates the biological plastic breakdown by marine fungi.”

Other fungi out there

As a large amount of different plastics sink into deeper layers before it is exposed to sunlight, P.album will not be able to break them all down. Vaksmaa expects that there are other, yet unknown, fungi out there that are degrading plastic as well, in deeper parts of the ocean. “Marine fungi can break down complex materials made of carbon. There are numerous amounts of marine fungi, so it is likely that in addition to the four species identified so far, other species also contribute to plastic degradation. There are still many questions about the dynamics of how plastic degradation takes place in deeper layers," says Vaksmaa.

Plastic soup

Finding plastic-degrading organisms is urgent. Every year, humans produce more than 400 billion kilograms of plastic, and this is expected to have at least triple by the year 2060. Much of the plastic waste ends up in the sea: from the poles to the tropics, it floats around in surface waters, reaches greater depths at sea and eventually falls down on the seafloor.

Vaksmaa: “Large amounts of plastics end up in subtropical gyres, ring-shaped currents in oceans in which seawater is almost stationary. That means once the plastic has been carried there, it gets trapped there. Some 80 million kilograms of floating plastic have already accumulated in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre in the Pacific Ocean alone, which is only one of the six large gyres worldwide.”

Schimmel breekt oceaanplastic af

Een schimmel die in de zee voorkomt, kan de plasticsoort polyethyleen afbreken nadat dit is blootgesteld aan UV-straling uit zonlicht. Dat blijkt uit onderzoek van onderzoekers van onder andere het NIOZ, dat is gepubliceerd in het tijdschrift Science of the Total Environment. De onderzoekers verwachten dat er nog veel meer plastic afbrekende schimmels leven in diepere delen van de oceaan.

De schimmel Parengyodontium album leeft samen met andere micro-organismen in dunne laagjes op plastic afval in de oceaan. Mariene microbiologen van het Koninklijk Nederlands Instituut voor Onderzoek der Zee (NIOZ) ontdekten dat de schimmel in staat is om deeltjes van het plastic polyethyleen (PE) af te breken, de meest voorkomende plastic van alle soorten die in de oceaan terecht zijn gekomen. De onderzoekers van het NIOZ werkten samen met collega’s van de Universiteit Utrecht, de stichting Ocean Cleanup en onderzoeksinstituten in Parijs, Kopenhagen en St. Gallen, Zwitserland. Deze soort schaart zich in een erg kort rijtje van plastic-afbrekende zeeschimmels: tot op heden zijn er pas vier soorten met deze eigenschap gevonden. Van een groter aantal bacteriën is al wel bekend dat ze plastic kunnen afbreken.

Afbraakproces nauwkeurig volgen

De onderzoekers gingen op zoek naar de plastic-afbrekende microben in de gyre in de Noordelijke Stille Oceaan, een ringvormige zeestroming waarbinnen het water bijna stilstaat. Uit het verzamelde plastic afval isoleerden ze de zeeschimmel door die in het laboratorium te kweken op speciaal plastic dat gelabelde koolstof bevat. Hoofdonderzoeker Annika Vaksmaa van het NIOZ legt uit: "Deze zogenaamde 13C-isotopen blijven traceerbaar in de voedselketen. Het is als een label waarmee we kunnen volgen waar de koolstof naartoe gaat. Vervolgens kunnen we het traceren in de afbraakproducten."

Vaksmaa is enthousiast over de nieuwe vondst: "Wat dit onderzoek wetenschappelijk interessant maakt, is dat we het afbraakproces kunnen kwantificeren.” In het laboratorium zagen Vaksmaa en haar collega’s dat P. Album het plastic PE afbrak met een snelheid van 0,05% per dag. “Bij het afbreken van PE komt koolstof vrij, maar onze metingen laten zien dat de schimmel daar zelf maar weinig van gebruikt. Het merendeel wordt door de schimmel omgezet naar CO2 en vervolgens weer uitgestoten.” CO2 is natuurlijk een broeikasgas is, maar de hoeveelheid die de schimmel uitstoot is maar heel klein, vergelijkbaar met wat mensen uitademen. Er wordt dus niet door de afbraak van plastic weer een nieuw probleem gecreëerd.

Alleen onder invloed van UV

De aanwezigheid van zonlicht is essentieel voor de schimmel om PE als energiebron te gebruiken, ontdekten de onderzoekers. Vaksmaa: "In het lab breekt P. album alleen PE af dat in elk geval voor een korte tijd is blootgesteld aan UV-licht. Dat betekent dat de schimmel in de oceaan alleen plastic kan afbreken als dat eerst dicht onder het oppervlak drijft. Het was al bekend dat UV-licht plastic zelf mechanisch afbreekt, maar onze resultaten laten zien dat dat op zijn beurt de biologische plasticafbraak door zeeschimmels makkelijker maakt."

Andere schimmels vinden

Omdat een grote hoeveelheid kunststoffen in de zee al naar diepere lagen zinkt voordat het aan zonlicht wordt blootgesteld, zal P.album niet in staat zijn om ze allemaal af te breken. Vaksmaa verwacht dat er andere, nog onbekende, schimmels zijn die plastic afbreken, dieper in de oceaan. "Zeeschimmels kunnen complexe materialen van koolstof afbreken. Er zijn talloze zeeschimmels, dus het is waarschijnlijk dat naast de vier tot nu toe geïdentificeerde soorten ook andere zeeschimmels plastic afbreken. Er is nog veel wat we niet weten over hoe plastic-afbraak in diepere lagen plaatsvindt", zegt Vaksmaa.

Plasticsoep

Het is dringend nodig om organismen te vinden die plastic afbreken. Elk jaar produceert de mens meer dan 400 miljard kilo plastic en de verwachting is dat dit tegen het jaar 2060 minstens verdrievoudigd zal zijn. Veel van het plastic afval komt in zee terecht: van de polen tot de tropen drijft het rond in het oppervlaktewater, bereikt grotere diepten in zee en komt uiteindelijk ook op de zeebodem.

Vaksmaa: "Grote hoeveelheden plastic komen terecht in subtropische gyres. Als het plastic die gyres eenmaal heeft bereikt, komt het vast te zitten. Zo'n 80 miljoen kilo drijvend plastic heeft zich alleen al opgehoopt in de North Pacific Subtropical Gyre in de Stille Oceaan, slechts één van de zes grote gyres wereldwijd."

Read the paper

The paper 'Biodegradation of polyethylene by the marine fungus Parengyodontium album' by A. Vaksmaa*, H. Vielfaure, L. Polerecky, M.V.M. Kienhuis, M.T.J. van der Meer*, T. Pflüger, M. Egger, and H. Niemann* was published in the scientific journal Science of the Total Environment in May 2024.