Deep sea microbes can adapt their basic building blocks - and why that’s special

Deep sea microbes can adapt their basic building blocks - and why that’s special

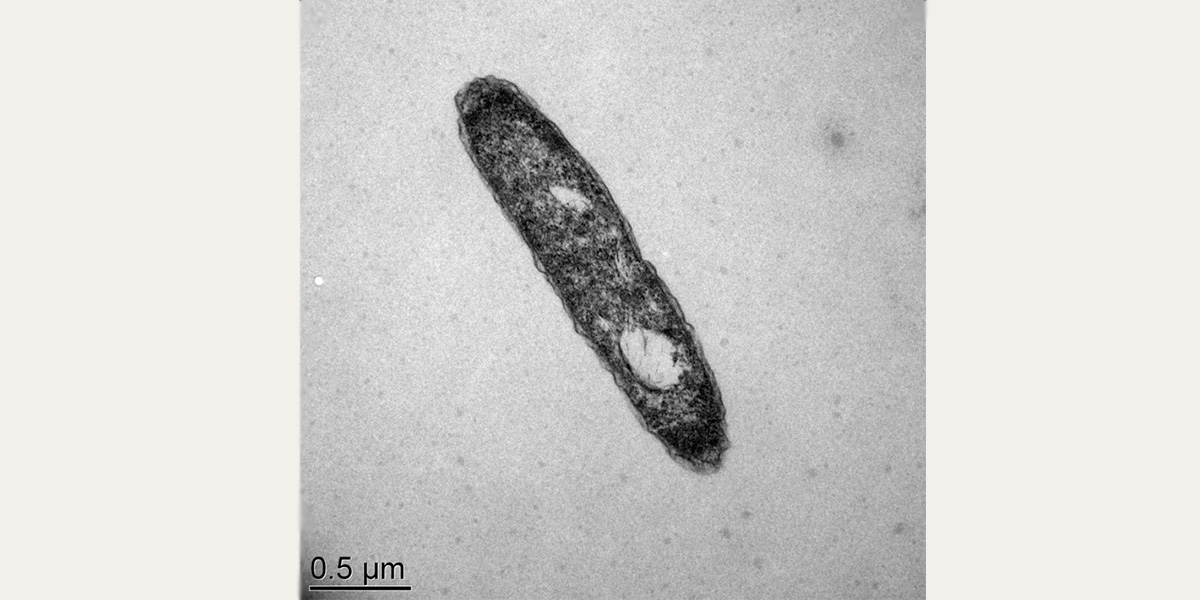

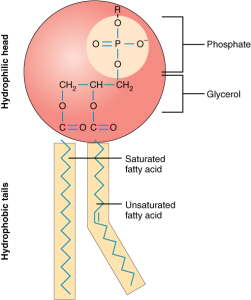

Microbes are organisms so small, you can’t see them with the naked eye. Many types of microbes consist of only one cell: think of bacteria that can cause an infection, but also the microbes that live in your gut and keep you healthy. Every microbe has a membrane that functions as a kind of 'skin'. The membrane provides the microbial cell's structure, protects its interior and regulates which substances enter and leave the cell. This membrane usually consists of phospholipids: ‘tails’ of fatty acids with a ‘head group’ containing the element phosphorus(see image). So phosphorus is essential for building the membrane of every cell. It also plays a major role as a component of DNA and in the energy management of cells.

Living without phosphorus

But what if a microbe lives in an environment where almost no phosphorus is present? A team of researchers from NIOZ (Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research), University of Lyon, University of Pau and Pays de l’Adour looked into the the marine bacterium Desulfatibacillum alkenivorans. They exposed this bacterium species to a wide variety of conditions, including shortages of nutrients such as phosphorus or nitrogen, as well as changes in temperature and acidity and salinity. They then analysed what happened to the bacterium's lipid membrane.

Working like a complex factory

To their surprise, in the near absence of phosphorus the bacterium was found to replace almost all the phospholipids in its membrane with novel lipids containing sulphur and nitrogen, elements which were available. "Apparently, this microbe is capable of adjusting the chemical composition of the cell’s membrane, so it can save the scarce phosphorus for even more essential cell ingredients such as DNA," explained NIOZ principal researcher Su Ding. "This change from phospholipids to sulphur and nitrogen lipids requires a huge coordinated adjustment of the whole cell system,” adds Jaap Sinnighe Damsté, supervisor of the research project. “It shows that such tiny microbes are actually working as a very complex factory."

Adjusting lipids to temperature

Ding and his colleagues also saw that a change in temperature caused the bacterium to change the composition of its lipid membrane. "This means that this bacterium found an entirely new way to adapt to difficult conditions," says Ding. This is relevant information: ocean warming and human activity – such as fish farms - can cause surpluses or shortages of nutrients. "Understanding better how bacteria adapt to these situations, can help us with strategies to counteract their unwanted effects on marine life. And by extension, also protect people and societies that depend on the sea for their livelihoods."

Unique technology

The research team used a unique technique to analyse the lipid membrane of the bacteria, developed at NIOZ a few years ago. This lipidomics method has a very high sensitivity and allowed the researchers, for the very first time, to analyse over 400 new lipids present in the bacterium, including those new nitrogen and sulphur lipids that replaced the phospholipids. The NIOZ laboratory is one in three laboratories worldwide that currently applies this technology. Earlier this year, they used this technology to uncover that parasitic archaea can be very picky eaters.

Microben in diepzee kunnen hun bouwstenen aanpassen – en waarom dat bijzonder is

Elke microbe maakt om zijn buitenste beschermlaag op te bouwen, gebruik van het element fosfor. Net als alle cellen in ons menselijk lichaam. Maar hoe doe je dat als er bijna geen fosfor in je omgeving is, zoals op bepaalde gebieden in de diepzee? Microbiologen van het NIOZ hebben nu aangetoond dat microben in die situatie de fosfor weten te vervangen door wat wél aanwezig is, zoals zwavel en stikstof. Dat geeft aanwijzingen hoe zeeorganismen zich kunnen aanpassen aan veranderende omstandigheden in de oceaan.

Microben zijn organismen die zo klein zijn dat je ze niet met het blote oog kunt zien. De meeste microben bestaan uit slechts één cel: denk aan bacteriën die een infectie kunnen veroorzaken, maar ook de microben die in je darmen leven en je gezond houden. Elke microbe heeft een membraan wat functioneert als een soort ‘huid’. Het membraan zorgt voor de structuur van de cel, beschermt zijn binnenste en reguleert welke stoffen de cel in en uit gaan. Dat membraan bestaat uit fosfolipiden: een verbinding tussen ‘staarten’ van vetzuren en een ‘hoofdgroep’ met daarin het element fosfor (zie afbeelding). Fosfor is dus een essentiële bouwsteen voor elke cel. Het speelt ook nog eens een grote rol in het DNA en de energiehuishouding van cellen.

Leven zonder fosfor

Maar wat als een microbe leeft in een omgeving waar bijna geen fosfor aanwezig is? Een team van onderzoekers, nam de diepzeebacterie Desulfatibacillum alkenivorans onder de loep. Ze stelden deze bloot aan steeds wisselende omstandigheden, waaronder te kort aan voedingsstoffen als fosfor of stikstof, maar ook wisselingen in temperatuur en zuur- en zoutgraad. Vervolgens analyseerden ze wat er gebeurde met het lipidenmembraan van de bacterie.

Als een complexe fabriek

Tot hun verbazing bleek de bacterie bij een gebrek aan fosfor bijna alle fosfolipiden in zijn membraan te vervangen door lipiden met zwavel en stikstof, stoffen die beiden wel voor handen waren. “Blijkbaar is deze bacterie in staat om de chemische samenstelling van zijn celmembraan aan te passen, zodat het het schaarse fosfor kan bewaren voor de meer essentiële onderdelen zoals DNA,” legt hoofdonderzoeker Ding uit. “Deze verandering van fosfor naar zwavel en stikstof vraagt een enorme, gecoördineerde aanpassing van het hele systeem van de cel,” vult supervisor Jaap Sinnighe Damste aan. “Het laat zien dat die kleine microben eigenlijk werken als een enorm complexe fabriek.”

Lipiden aanpassen aan temperatuur

Ding en zijn collega’s zagen ook dat een verandering in temperatuur zorgde dat de bacterie de samenstelling van zijn lipidenmembraan ging aanpassen. “Dit betekent dat deze bacterie een geheel nieuwe manier heeft gevonden om zich aan te passen aan moeilijke omstandigheden,” aldus hoofdonderzoeker Ding. Dat is relevante informatie: de opwarming van de oceaan en menselijke activiteit zoals viskwekerijen kunnen zorgen voor overschotten of juist tekorten aan voedingstoffen. “Meer inzicht in hoe bacteriën zich aanpassen aan deze situaties kan ons helpen in het ontwikkelen van strategieën om ongewenste effecten ervan op het leven in zee tegen te gaan. En in het verlengde daarvan ook mensen en samenlevingen te beschermen die afhankelijk zijn van de zee voor hun levensonderhoud.”

Unieke technologie

Het onderzoeksteam gebruikte een unieke techniek om het lipidenmembraan van de bacterie te analyseren, die enkele jaren geleden op het NIOZ is ontwikkeld. Deze lipidomics methode heeft een zeer hoge gevoeligheid, waarmee het team voor het eerst meer dan 400 nieuwe lipiden in de bacterie kon analyseren. Waaronder dus de nieuw gevonden zwavel-stikstoflipiden ter vervanging van de fosfolipiden. Het NIOZ is momenteel een van de drie instituten wereldwijd die deze techniek inzetten. Eerder dit jaar ontdekten Su Ding en collega’s met deze technologie dat parasitaire archea nogal kieskeurige eters zijn.

The study ‘Nitrogen and sulfur for phosphorus: Lipidome adaptation of anaerobic sulfate-reducing bacteria in phosphorus-deprived conditions’ was published on 5 June 2024 in the journal PNAS.

The research was a collaboration between NIOZ (Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research), University of Lyon, University of Pau and Pays de l’Adour.

doi: 10.1073/pnas.2400711121