30 August 2024

By Geert de Bruin

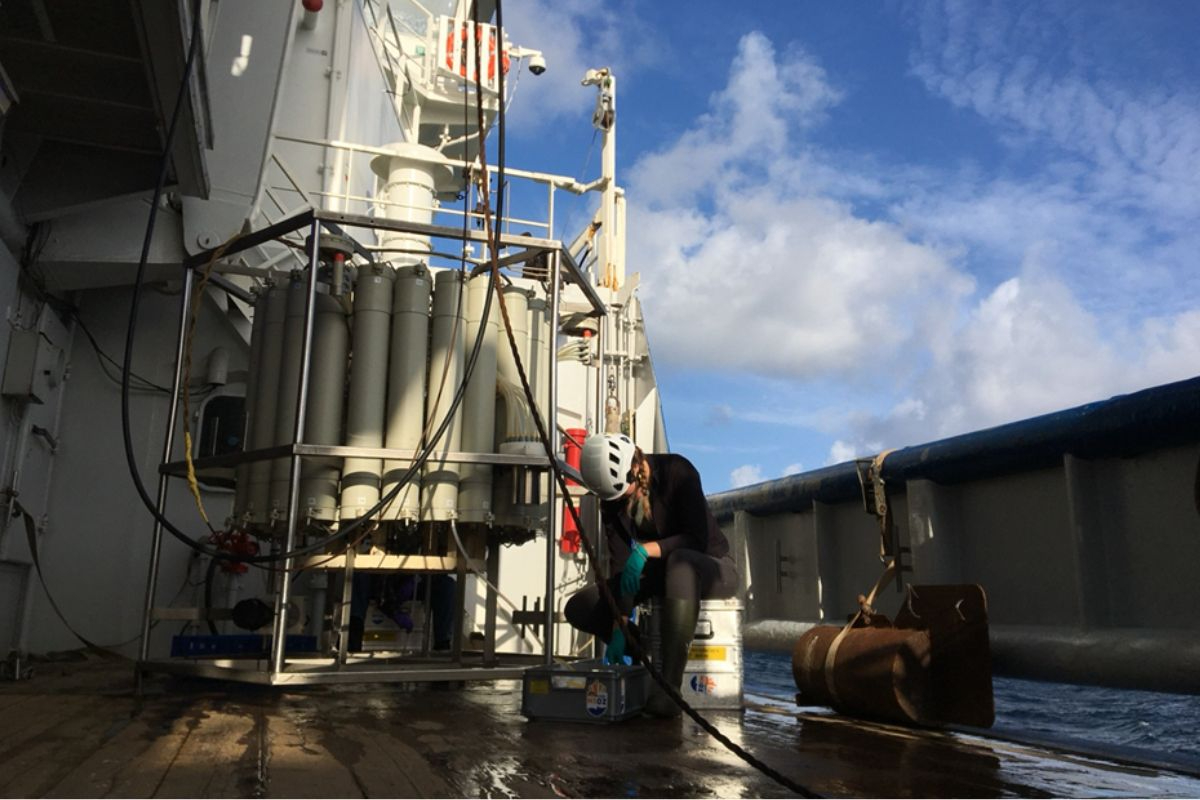

Measuring methane emissions at sea is easier said than done. Even when the Pelagia is directly over a leaking well, there is still a water column of 40 to 50 meter between the ship and the seabed. To bridge this gap, we use landers that are placed on the sea floor, that can measure a wide array of parameters. These landers are carefully designed and build in-house by NIOZ. Since communication with the lander is not possible once they are in the water, they are designed to work autonomously. This requires meticulous planning, clever designing, and rigorous testing in the test basin to see whether the landers functions as intended.

For this measuring campaign NIOZ specifically designed and build two landers. The first is a mini-lander that has a whole array of sensors mounted on it. It has a HD camera to film the bubbles, a methane sensor that measures dissolved methane, a current sensor, a depth sensor that can measure waves and tides, and a hydrophone (an underwater microphone) that records the sound that bubbles make. The second lander is a large funnel that catches the bubbles and measure the volume of gas that is coming from the seabed. Both landers are left on the seafloor for a couple of days. The reason for this is that we expect variations with tides. With low tide the pressure is lower, and as everybody knows from opening a bottle of sparkling water, lower pressures mean more bubbles.

Deploying the landers is always very exciting, since the landers position is critical. Is the funnel directly over the bubbles? Is the camera pointing towards the bubbles? This requires close collaboration between various teams. We use an underwater robot, called a remotely operated vehicle (ROV), to guide the lander to the right spot. The ROV is our eyes on the seafloor and therefor the operator can instruct the bridge to steer the ship in the right direction while simultaneously instruct the winch operator when to lower the lander. Everybody is fully concentrated and when the landing was successful, the relieve is very high. “Houston, the eagle has landed”.

When the lander is brought back on board, expectations are also high. You never know if the lander performs the way it was intended. Sea conditions are very different than the NIOZ test basin. Sand, waves, currents, low visibility, hard landings, can’t be replicated in the test basin. Looking at the first results is like having a film roll developed, and you see the pictures for the first time. Did we succeed? Was all the work rewarded?

28 August 2024

By Robin van Dijk

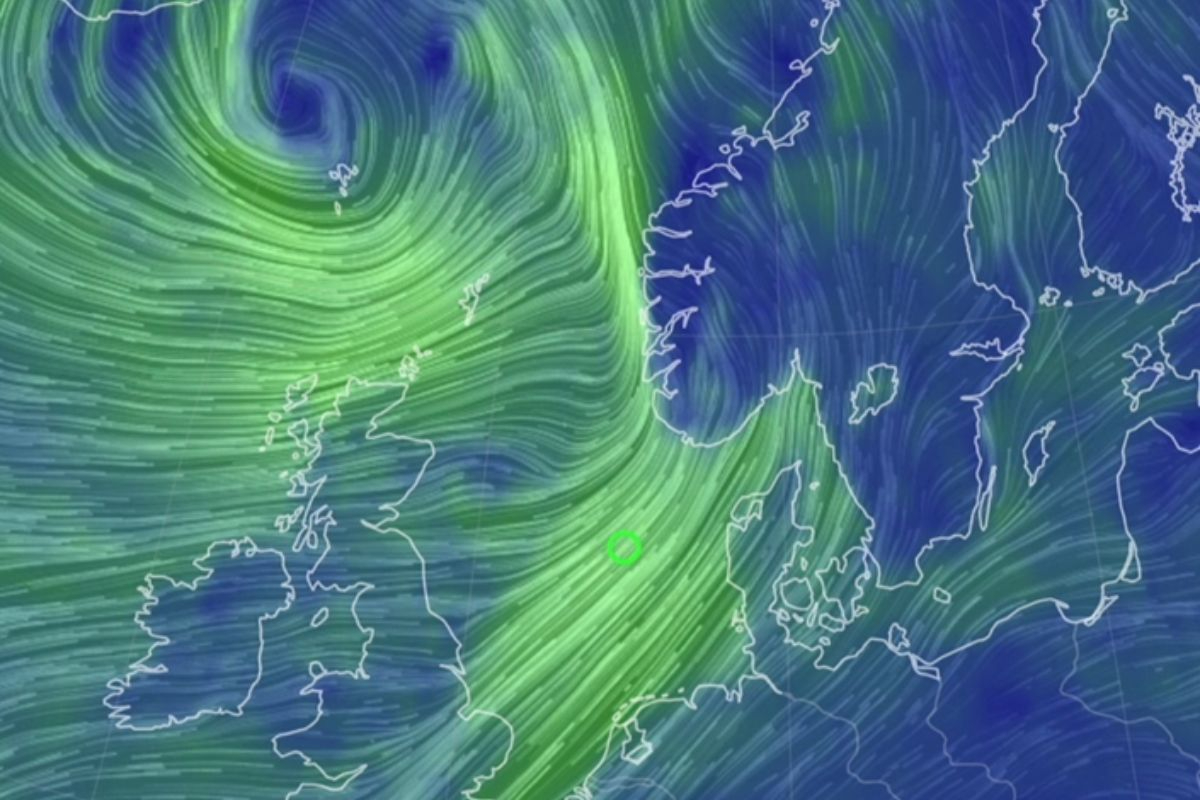

At this moment our final week on the Pelagia is about to start. In the past 1.5 week we have had successes, our flexibility was tested, and definitely some bumps at sea. It almost looked like the North Sea was treating us well in terms of the weather compared to last year. Conditions with only little swell makes working at sea very pleasant. However, even in summertime the North Sea can be rather unpredictable. Just before the weekend we had to escape our study location in the center of the North Sea due to a powerful storm that was headed our way.

But let’s start at the beginning of last week. Just prior to the storm we performed two cycles of 24-hour continuous CTD measurements and sampling to capture the influence of the tide on the methane emissions from the seafloor. Both the CTD team as well as the deck’s crew can luckily divide this 24-hour cycle up, so we all get our well-deserved hours of rest. A good combination of experienced CTD team members that also joined the similar voyage last year, and new members that were excited to learn more about seawater sampling led to joyous and efficient sampling.

But the storm that was headed our way, just when we finished the CTD sampling, deserves some mentioning. This storm that hit most of eastern Europe is a remnant of hurricane Ernesto that travelled from Florida up the entire east coast of the US to Canada. It developed hurricane strength again, bringing high waves and strong winds to our sampling location right in the eye of the storm. This was not a good place to sit it out, so we travelled north to escape the heaviest conditions. Although most of us enjoyed some of the rough weather (because what is a voyage on the North Sea without a proper storm?), others were a bit more silent during the meals and kept their focus solely on the horizon. With the storm travelling more eastward and leaving the North Sea we dared to make our way back. We were accompanied by some blue skies and even some of us caught a glimpse of some dolphins playing in the waves. But mostly, we were all looking forward to continuing the sampling on this voyage.

23 August - Methane expedition | Summer edition

By Annalisa Delre, PhD Student at NIOZ

And here we are, once again in the North Sea looking for methane bubbles. It is summer, mild temperatures, the right amount of vitamin D, the North Sea still being kind to us - so far so good. Of course there have been multiple changes of plans, some things get broken, some things don’t work at first, but nothing too serious that can’t be fixed, and nothing that makes me think: ‘I will never have enough samples to finish my PhD’.

This is my second time on an expedition, and my goal is to understand how much of the methane that is liberated from the sea floor is ‘eaten’ by microbes. But this ship is not only a working platform, I’m also living here during the expedition. I have always seen the Pelagia crew as an extended family, people who live and work closely together for weeks on end and who sometimes have to (fortunately or unfortunately) share this already limited space with scientists. So, what do they think about us scientist? I would have liked to ask many questions, but it would have been difficult to maintain anonymity. So, I asked the whole crew the same question: ‘What do you appreciate about having scientists on board?’. I thought it was a rather simple question, but looking at their reaction I realised that we scientists are not easy people at all.

I got several and varied answers. Of course, the most classic one I would have expected from all of them is ‘if you don't complain too much, working with you is fine’. How can you blame them?! Most of the crew seem to be excited to share a few weeks with new people, to understand our projects and who is behind that ‘scientist mask’. It is really gratifying to see them so involved. For those who have worked in commercial vessels, they appreciate the difference. Some appreciate our curiosity, not only in our work but also in asking questions about the tools used by the crew (learning how to tie knots seems to be very much in vogue). Ah of course, don't forget to warn the cook and steward in good time if any of the scientists have to eat before or after meal times! Essential information for the respect of their hard work. I quote one of the crew who left me a message that perhaps sums it up; "I very much like meeting all those people with their different personalities, backgrounds and habits. How we all deal differently in certain situations. To see how we interact, all working together as a team. To make the best out of a cruise, both socially as well as in terms of scientific results. I like the challenges it brings and to keep learning from it”. I, for one, am extremely grateful for their help and also the help of everyone in this cruise and in his preparation.

19 August 2024 - The Ship That Never Sleeps

By Helge Niemann - Expedition Leader

The first days of our expedition have passed in a blur aboard the R/V Pelagia, the flagship of the Netherlands' research fleet. For the next two weeks, she will be our home as we navigate the central North Sea. But as always, our story began long before we arrived here.

Let’s rewind the clock...

The North Sea is one of the busiest seas in the world. An endless stream of cargo ships transports goods to and from Europe’s major ports, and growing wind farms generate much-needed electricity. Yet beneath the seabed lies an older energy reserve: natural gas. This gas has its origins in deep geological time, so let's go back millions of years, to a time long before humans roamed our blue planet.

When the North Sea was young, and even before that, when a shallow ocean covered the area now known as the North Sea, vast amounts of organic material—plankton and algae—sank to the seabed and were buried under layers of sediment. As time passed, the organic material was either degraded by microbes or the pressure and heat hundreds of metres below the seabed ripped the complex organic molecules apart, ultimately leaving behind natural gas: methane.

Today, thousands of platforms scattered across the North Sea exploit these gas deposits to feed our insatiable energy demands. However, nothing lasts forever. Once a reservoir is no longer economically viable, platforms are decommissioned and the boreholes are sealed.

This brings us back to the purpose of our expedition. When a reservoir is depleted, some gas remains, and recent scientific findings suggest that some of these old boreholes may be leaking. This discovery has raised concerns among scientists, policymakers, and the public alike, as methane is a potent greenhouse gas—about 30 times more effective at trapping heat than CO₂.

With so many boreholes in the North Sea, many of which have already been sealed, and many more to be sealed in the future, the question arises: How much of this greenhouse gas is escaping into the sea and potentially into the atmosphere?

To answer this, our team—a collaboration of scientists from the NIOZ (Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research), TNO (Netherlands Organisation for Applied Scientific Research), and SodM (a subsection of the Dutch Ministry of Economic Affairs)—is conducting a series of measurements at old boreholes in the Dutch sector of the North Sea. During this expedition, we will spend the next two weeks measuring methane in the seabed, the water column, and the atmosphere. We will investigate microbes that can degrade methane and thus play a crucial role in shielding the atmosphere from this greenhouse gas. During this expedition, we will breathe science. Teams will hand over tasks as watches change aboard the ship that never sleeps—the R/V Pelagia.