Introduction EASI-2 East Antarctic expedition

On the German icebreaker RV Polarstern, we will cross the Indian sector of the Southern Ocean, from Cape Town (South Africa) to the continental shelf of East Antarctica. Along the continental shelf, we will sample near multiple ice shelves, some of which are melting fast right now. From there, we will sail to Hobart (Australia) where we end our journey. During the 10-week expedition, we will collect seawater (Rob & Florine) and sediment (Wytze) samples for trace metal analysis, and conduct incubation experiments to determine which trace metals limit phytoplankton growth in which parts of our study region (Robin). We will also work closely together with the other 44 scientists on board, for instance on the incubation experiments and through sharing our seawater samples. Through this blog, we will keep you updated on our journey.

Week 7: Final blog

Introduction

In the last blog, I wrote about our final moments in the Antarctic coastal waters – tomorrow, we will have our final moments on the Polarstern! The storage container is filled to the brim with seawater samples, and all our cargo is stored away for the journey back home. Yesterday, on the 30th of January, we arrived in Hobart, Tasmania. The same afternoon we were allowed to leave the ship – this resulted in a rush to the Australian supermarkets to score fresh fruit and vegetables after weeks of canned and pickled food. It was excellent! Today, we are bunkering, meaning that the Polarstern is being refueled. Tomorrow, we will officially disembark and go our separate ways.

During the expedition, we have worked very hard, and this has paid off: we did 51 clean CTD casts in 54 days of sampling, much more than we expected beforehand. After Titan’s hiccups in the beginning, resulting in 3 failed casts, all other casts were successful. In total, we collected trace metal samples at 47 stations, had a successful shallow cast to collect seawater for bioassay experiments, and conducted 33 bioassays of 72 hours, 3 longer bioassays and an incubation experiment with seawater bacteria collected from 4 different stations. All samples from the clean CTD and subsequent experiments are now ready to be analyzed back to Europe. Although analyzing will take quite some time, we are expecting some interesting results.

This is the last blog entry of the EASI-2 expedition, and therefore we would like to end this story with some personal reflections on the expedition of each member of the Trace Metal Team.

Florine Kooij

The last 70 days were indescribable. This was my first expedition and I was very nervous beforehand, but I immediately felt at home on the Polarstern – also thanks to the amazing crew! The work was much more physically demanding than my regular office and laboratory work, with much higher chances of getting blasted by ice-cold ocean water, but I enjoyed it very much. In the beginning, all the different steps of the CTD casting and sampling were overwhelming, but soon we all worked together smoothly, with only some mild bickering over our differing music choices. Speaking of music, I also loved our world-shattering (or at least ear-shattering) karaoke performance. Generally, the atmosphere on board was really good, ‘gezellig’, and it will be hard to let go tomorrow when we leave the ship! However, I’m also excited to have a break before starting the analysis of the trace metal samples back at NIOZ. While we were immersed in the Antarctic wilderness, we also saw signs of climate change and ice shelf melt during the expedition, and I hope our research can help to understand this better, so we know what to expect in the future and what we can still save if we act now to mitigate further climate change.

Wytze Lenstra

Going ten weeks on a research expedition to Antarctica is one of the most special things I have ever done. Collecting samples from the seafloor in places that were never sampled before is truly something special. I was very lucky to be surrounded by a great team that was always ready to help wherever. I will never forget the sound of the phone ringing at 3 AM “hello, the multicore is almost on deck” and the subsequent suspense of waiting for the multicore to come up the last few hundred meters. Did it work? How do the sediments look? After this very successful expedition I am very excited to start working on the samples back in the Netherlands at the Radboud University and also happy to go back home to see my family again.

Jasmin Stimpfle

Disembarking Polarstern after 10 weeks, I’m looking back to an incredible journey, filled with hard work, great team spirit and breathtaking landscapes. I’m very grateful for all the new things I learned and for all the motivated members in our team that made long shifts still enjoyable. Laughing at stupid jokes while sitting cramped together at a tiny clean bench in the middle of the night or doing penguin dances in the clean container to warm up, is what I’ll keep in good memory. Although I’m missing the beautiful and pristine wilderness of Antarctica, I’m happy to go home now and I’m very curious what the results of our hard work will bring us.

Marrit Jacob

After my first ever scientific cruise, I am returning to land with lots of respect and admiration for seafaring and field work in the beautiful, harsh polar environments, and in absolute awe of our incredible planet. Every sighting of a penguin and every iceberg we passed on our journey, every ice floe and whale, every gentle roll of the ship during ice-breaking and every small or big success during our team’s research activities over the last 10 weeks made up for the hard work, long night shifts, and sleep deprivation. The great teamwork and good spirit and the determined and kind support of the crew of RV Polarstern made for a fantastic work environment and enabled an amount of scientific output, that exceeded our expectations. Our research efforts will keep us busy for years to come. Our memories of witnessing the beautiful vastness of Antarctica will hopefully stay with us forever and provide the endless motivation needed to keep on working hard, documenting and protecting the invaluable ecosystems that sustain the health of our planet. I will return with lots of samples, new friendships, and a big Antarctica-shaped hole in my heart.

Rob Middag

What an expedition it has been! I had the honor of leading a great team of early career scientists on this expedition and due to their perseverance and dedication, we achieved way more than we originally planned. For me it was not the first time to visit this amazing continent, but the magnificent wildlife, breath taking scenery and sheer power of the ocean and ice are an absolute privilege to observe, no matter how many times you see it. It makes one feel very special to know you are visiting one of the most remote places one earth, one of the last places that has not been obviously impacted by human presence. Unfortunately, closer inspection tells us even the Antarctic is suffering from human activities; man made plastic and other pollutants are found and the climate is changing rapidly. The impacts of human activities on this unique ecosystem are not yet fully known, but our expedition and research will contribute to our understanding of Antarctica and how we are affecting it. And hopefully, more knowledge will not only lead to more understanding and awareness, but also to more action to preserve our unique planet. After all, we only have one Earth and an expedition to the Antarctic and stormy Southern Ocean definitely teaches you to respect the beauty and power of our planet!

Last but not least, I would not only like to thank my team on board, but also everyone else who made this expedition possible. The officers and crew of the magnificent Polarstern as well as our fellow scientists, notably Chief Scientist Marcus Gutjahr, made the shipboard work not only possible, but also very enjoyable. The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research provided the required funding and our colleagues at the Royal NIOZ and AWI were absolutely crucial in the preparations beforehand to make the work possible.

Finally, we left family and loved ones behind to work in the Antarctic, where contact was restricted. Their encouragement during setbacks or long working hours was invaluable and kept us going, so a big thank you for all your support!

Week 6: Goodbye Antarctica!

By Florine Kooij

As I’m writing this, we have said goodbye to Antarctica and are sailing north again, this time to Hobart, Australia. Back on the continental shelf (relatively shallow seas near the continent), there were virtually no waves due to dampening by sea ice, but now we are back in choppy waters. And after weeks of polar day, when the sun was up 24 hours per day, it was also surprisingly tough to transition to a normal day-night cycle, especially while also shifting time zones every few days. But we are getting back in the rhythm, and we are approaching the end of our sampling campaign. Great, because we are almost running out of bottles!

Along the continental shelf, we had the chance to sample near two ice shelves: the Amery and the Shackleton ice shelves. These ice shelves are giant slabs of ice that act as barriers to the glaciers behind them, preventing the glaciers from flowing into the ocean and raising global sea level. The Amery ice shelf, situated in Prydz Bay, is Antarctica’s third-largest ice shelf: one and a half times as big as the Netherlands! The Shackleton ice shelf is about half the size of the Amery ice shelf, and it is located farther north with only a narrow continental shelf in front of it. It has recently been discovered that warm ocean water intrudes onto the continental shelf through an underwater canyon, where it can melt the ice shelf from below. During our CTD casts, we found this warm water layer, as well as ice cold water coming from fresh glacial melt. While concerning, glacial melt is also a potential source of trace metals, so comparing the fast-melting Shackleton ice shelf with the ‘steady’ Amery ice shelf could give us important insights into trace metal release in a future with more ice shelf melt. Right now, they are both standing tall, and they have given us incredible views when we were still on the continental shelf.

Although we had enough time to enjoy the beautiful surroundings of the Antarctic coastal waters, a lot of our time was spent sampling the clean CTD in the cleanroom container. In here, we wear hairnets and special clean suits, to prevent contaminating the samples. Below those, everyone wears thermal clothing – we try to keep the temperature in the container as close as possible to the water temperature, which can be as cold as -1.9 °C near the coast! In the container, we start with the colloquially termed ‘dirty’ work, where trace metal contamination is not a threat yet: amongst others, we take samples for oxygen concentration, salinity and nutrients. Then, we don a new pair of gloves and the trace metal-clean work starts.

To understand the dynamics of trace metals in the Southern Ocean, we look both at dissolved and particulate trace metals. For the dissolved trace metals, we collect filtered seawater, which we later acidify to keep the metals in solution. In our storage, we now have hundreds of bottles ready to be analyzed back at NIOZ. For the particulate metals, we filter seawater over disc filters and store these filters for later analysis. For this filtration, we have a custom-made system (see picture below). First, we fill some large carboys with a few liters of seawater, and put filters on the cap. Thereafter the carboys are hung upside-down and put under gas pressure and the water flows through the filters without further input required. While the filtration runs for two hours, we can leave and process our other samples, or simply take a break and warm up a bit. When we collect the filters after the filtration, you can immediately see which filters come from the surface waters: these filters are completely covered in yellow or green phytoplankton. This is another big difference with the open ocean waters: there is a lot less phytoplankton here. Soon, with on-board bioassays and seawater measurements back at NIOZ, we hope to find out if this is indeed due to trace metal limitation!

Week 5: Science and scenery in Prydz Bay

By Jasmin Stimpfle and Marrit Jacob

We have now been spending almost 3 weeks exploring the scenic Prydz Bay in Eastern Antarctica, where we have been taking samples from different water masses and the sea floor sediments throughout the bay. The cruise track getting here led us from the vast open ocean, across regions of small ice floes into dense sea ice along icebergs, and eventually very close to the impressive Antarctic ice shelf. The trip required quite some ice-breaking, which our marvellous research vessel Polarstern managed effortlessly, and made for gorgeous views of the different environments as well as a lot of very interesting material for our research. Curious penguins were often watching us while we were taking our samples. We got to spend Christmas and New Year’s onboard the ship in this beautiful icy region, which was celebrated with festive food, some music by the ship’s choir, a gift exchange, dancing, and celebratory preparation of oliebollen by the Trace Metal Team. We started 2024 in bright sunlight, enjoying the perks of the polar day among magnificent icebergs and with lots of penguins around!

Our experiments continued during the festivities of Christmas and New Year’s and our climate room was packed with incubation bottles, containing microscopic algae (phytoplankton). These are grown under different conditions to study the impact of trace metal limitation on these important oxygen producers in a changing environment, as well as interactions between the algae and their associated bacteria. Like all living beings, algae need certain nutrients to grow. Two of them, which are extremely scarce in open waters of the Southern Ocean, are iron and manganese. We want to find out how this limitation, combined with predicted changes in light availability (needed for photosynthesis) will affect algae and their associated bacteria, as these small organisms play a vital role in balancing our earth’s climate. Carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is taken up by the ocean and turned into organic material by algae through photosynthesis. As the basis of the marine food web, algae are then either eaten by animals or eventually sink to the seafloor after they die. This process stores carbon in the deep sea, and a substantial proportion of this carbon removal from the atmosphere happens in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica. This, however, might be affected by ongoing climate change that will alter availability of light and trace metals, including iron and manganese, with currently largely unknown consequences for both the climate as well as the unique Antarctic ecosystem.

Week 4: Arriving in Prydz Bay

By Wytze Lenstra

After weeks at the open ocean with only water in sight, the first iceberg of our research cruise was spotted on the 12th of December. The following days more and more sea-ice and icebergs surrounded us and with this ice also the amount of sea life increased. Adelie penguins, Humpback whales and seals greeted us on our journey towards East-Antarctica and in the early morning of the 17th of December we arrived in Prydz Bay. This is one of the key study locations of our research cruise where we will spend three weeks to investigate how changes in climate impacted the Eastern Antarctic Ice Sheet in the past and how this coastal zone currently affects nutrient cycles in the Southern Ocean.

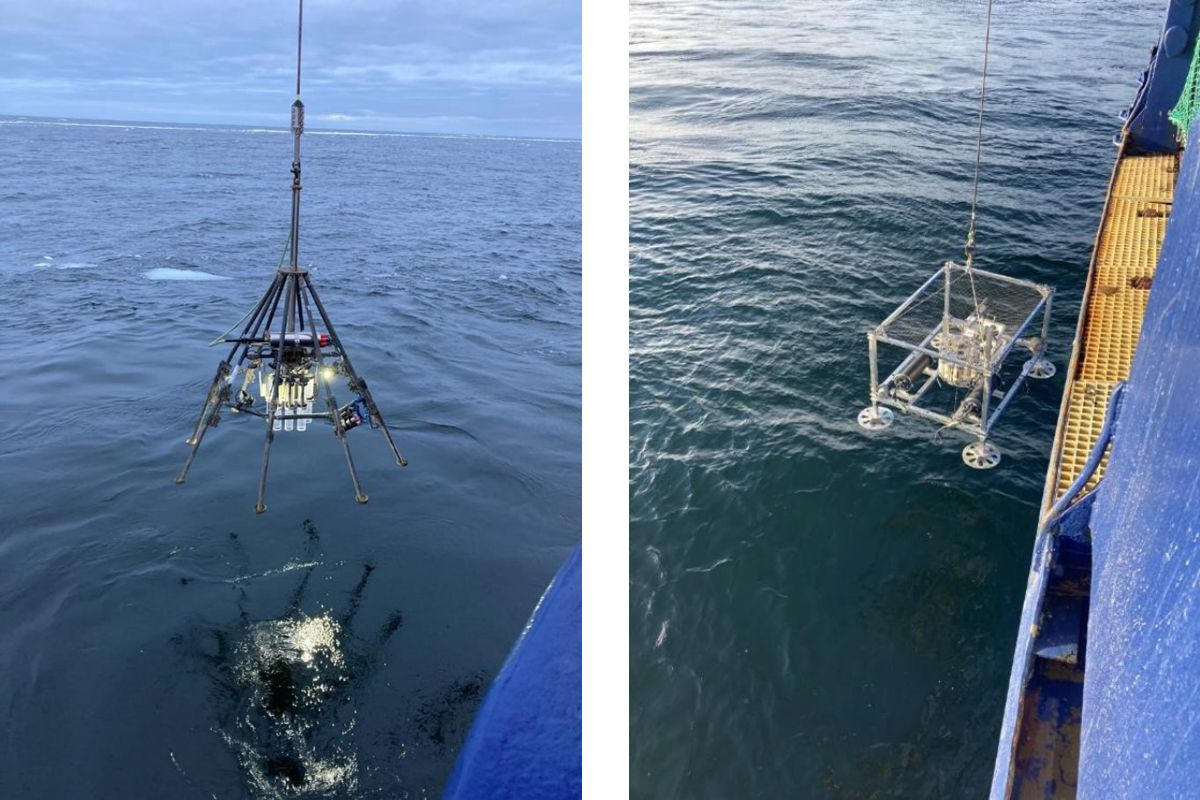

Besides all the water column work that has already been done, now our research will also focus on the seafloor because this can be an important source of nutrients to the open ocean. To sample the seafloor we use a multi-corer that collects approximately the first 30 cm of the sediment in core-liners (tubes). Once our sediment samples are onboard these are quickly brought to one of the lab containers on board, in which we further process the samples in conditions that simulate the conditions at the seafloor. This means that all work is carried out at bottom water temperature, which is currently around the freezing point, and in so called glove-bags which are filled with argon to avoid any contact of our sediment samples with oxygen. In this way we keep our samples pristine and we are able to determine which processes are currently taking place in the sediment.

To determine the importance of the seafloor as a source of nutrients to the ocean, we also use a so-called benthic lander. This is a device that is placed on the seafloor for approximately 8 hours and during this time the lander autonomously takes water samples from just above the seafloor. With these samples we are able to calculate how much nutrients are currently coming from the seafloor. The coming weeks will be intense where we will sometimes sample multiple stations at one day until we leave East-Antarctica again and will sail again towards to open ocean.

Week 3: Surviving the roaring forties and screaming fifties

By Rob Middag

We have had an eventful week while traversing the latitudes known to mariners as the roaring forties and screaming fifties, a region of the Southern Ocean infamous for its strong winds. These are caused by the combination of air that is travelling towards the south pole, the rotation of the earth, and the scarcity of landmasses to serve as windbreaks at these latitudes. To protect our precious clean lab container on the working deck there is a sturdy ‘seawall’ that consists of metal beams, and we sure needed that as some of these thick beams were bent by the force of the waves! The wall did its job and our container did not have a scratch on it, so after the waves died down, we could continue with our work.

Unfortunately, our trace-metal clean CTD, that is nicknamed Titan as it is constructed out of titanium, seemed to have gotten a bad case of seasickness during the storms. After its first deep dive post-storm to almost 4500 m, Titan came up with all its samplers still open… This meant there was no water to use for experiments and measurements, which was very disappointing indeed. There was no obvious reason for this malfunctioning, so we cleaned and greased the appropriate components of the hydraulic mechanism that is responsible for closing the samplers and did a test deployment down to 500 m. This was successful and gave us water to start some new bioassay experiments. Encouraged by this test we were optimistic about the next deep deployment to 4400 m, but Titan came back up empty again!

This was a major problem as many scientists on the ship rely on Titan to provide them with clean water for their measurements and experiments. So, we opened up our box with spare parts and consulted with our colleagues at NIOZ about which parts we should replace. Since Titan has to fit inside the clean container, some parts are not so easy to reach or replace, especially not on a moving ship, but we managed and were anxiously waiting for the next deployment. The ocean was not so deep at this location, ‘only’ 2200 m, but this still takes quite some time as the system descends and ascends with a maximum speed of 1 meter per second. During the deployment we were all nervously waiting for Titan to surface again and it was an enormous relief to see Titan surface with all 24 samplers neatly closed! It was already late in the evening, but nobody minded working into the night to process our precious water from all depths of the ocean once again. Currently we have had 4 successful deployments in a row, so we are back on track and happily sampling and processing samples on our way to the Antarctic continent.

Week 2: First sampling stations and storm

By Robin van Dijk

While we find ourselves at open seas and cruising toward the Antarctic continent, we have multiple sampling stations planned along the way. Each station on the open ocean consists of 13 hours of deployments for all the different science groups on board, and afterwards even more hours of processing the samples. While we are getting used to living at sea, the sun is still accompanying us, and the ocean remains surprisingly calm. Yet, as we travel further south, a storm awaits us, promising waves reaching 6 meters and winds gusting with 100 km/h.

Our diverse team on board comprises marine and land geologists, a water sampling team, and our Trace Metal team consisting of the Dutch scientists, and Jasmin and Marrit from AWI and University of Bremen. Equipped with the trace-metal clean water sampler (CTD) from NIOZ, we will operate at every station to get a better insight in the trace metal availability in this section of the Southern Ocean. Once on deck, we transfer the entire CTD into a clean container. Inside the container, our team diligently works, while others transport the water samples to the laboratories for filtrations, measurements, and the initiation of phytoplankton experiments.

Navigating through the Roaring 40s, where powerful westerly winds reign between the latitudes of 40° and 50° in the Southern Hemisphere, we were confronted by our first storm. Deck operations, including sampling stations, came to a temporary halt as waves crashed onto the deck in a spectacular display. The once radiant sun was replaced by snow and hail, accompanied by wind speeds of 10 Beaufort. While witnessing the forces of nature, we eagerly want to resume our work along this transect before reaching the continent of Antarctica.

Week 1, boarding the RV Polar Stern in Cape Town

By Florine Kooij

After months of packing and preparing, we finally flew to Cape Town on the 23rd of November. Coming from the dreary Dutch autumn weather, the South-African spring was a very warm welcome! We had one day in the city before boarding the Polarstern, so Robin and I took the cable cart to Table Mountain and went for a walk on the top. From up there, we could see the ship in the harbor below us, even from a thousand meters higher. The rest of Cape Town was also very beautiful, with lots of incredible nature, so we could soak up some green before heading to the Antarctic.

The next day, we could board the Polarstern. It is an impressive ship, 118 m long and 6 decks high. Very spacious, so a good space to call home for the coming months. Due to some final reparations of the ship, our departure was delayed by a few days, giving us the time to unpack our cargo and set up the lab spaces. We also got to know the other scientists joining the expedition: we have a nice mixture of people from different disciplines from all scientific career levels. It was a lot of work to move around our heavy equipment, organize everything and prepare the clean CTD, so I was glad to do that without additional difficulties from rough ship movements. However, I was even more glad when we could set sail yesterday evening, on November 28th. After a last look on Cape Town, we’ll mostly see water for the coming time – it will be a while before we reach Antarctica! Right now, I’m still getting used to the waves, which are already spilling onto the working deck from time to time. Walking in a straight line is a bit challenging, so I’m zig-zagging my way through the ship. The Polarstern is cruising fast to make up for lost time, and if all goes to plan we’ll reach the first research station by tomorrow. Then, the real research will start!