MSc. Tjitske Kooistra

Filling the marine sandbox and life on the seafloor

Seafloor animals like razor clams and cockles have a strong relationship with their environment: their habitat is determined by the sediment type, and vice versa, they can also influence the stability and composition of the sediment themselves. As you can imagine, the large amounts of sand that we use to protect our coasts, are of great potential influence on the life of these animals. I am studying the two-way traffic between sand and seafloor animals.

Sand nourishments protect our coasts

In 2018-2019, 5 million m3 sand was placed at the Ameland ebb-tidal delta, between the Dutch Wadden islands of Terschelling and Ameland. This so-called ebb-tidal delta nourishment is supposed to counteract coastal erosion in the Wadden Sea area: as the water current redistributes the sand, it will enable the long-term protection of the islands and tidal flats.

Understanding the interactions between sand and seafloor animals

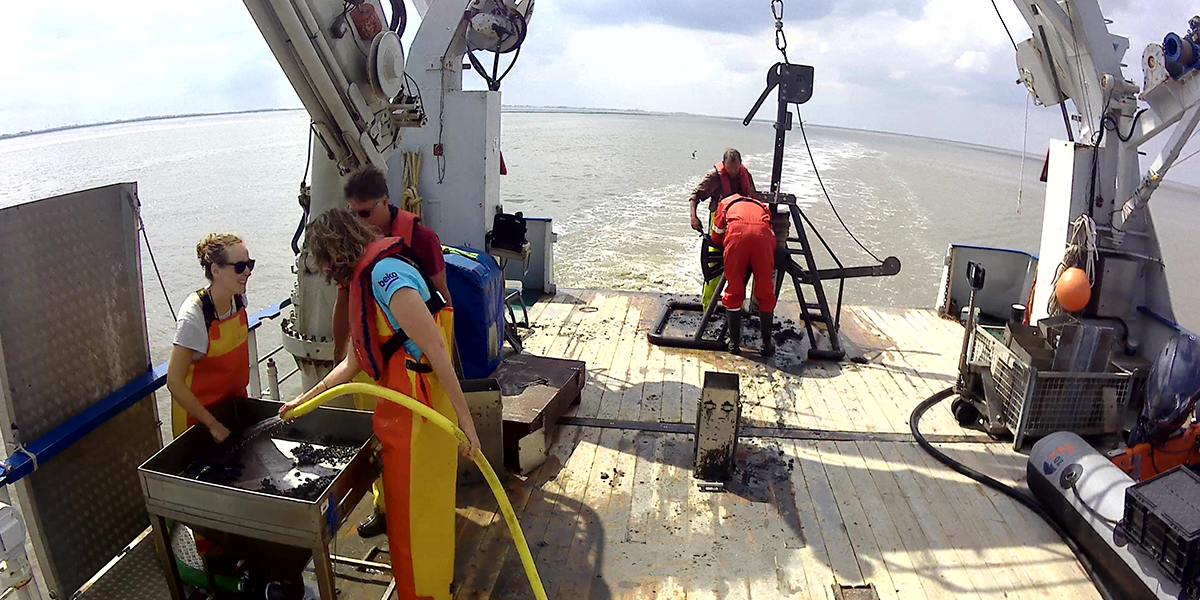

However, filling the sandbox can impact animals in the sediment. Bivalves, crustaceans and worms that live on or just below the seafloor, so-called benthos, will suddenly be buried or no longer be able to filter the water for food. This new type of sand nourishment is placed directly at the entrance of the Wadden Sea and we don’t know exactly how it impacts the benthic communities and habitats away from the nourishment, or whether the animals might even influence the transport and composition of the sediment themselves. In my research, I study the two-way traffic between the sediment and seafloor animals. I use field data of benthos in the Wadden Sea, and perform field and lab experiments with bivalves such as razor clams (Ensis leii), cockles (Cerastoderma edule) and Baltic tellins (Limecola balthica) and worms such as the lugworm (Arenicola marina).

My PhD is part of the interdisciplinary project TRAILS (TRacking Ameland Inlet Living lab Sediment), funded by NWO Living Labs in the Dutch Delta, which focusses on the sand transport and impacts of an ebb-tidal delta nourishment.